I’ve been thinking a bit about inductors and capacitors lately and wanted to share some nice facts about them. But to start with, what exactly is a capacitor? Well, it’s a thing that stores charge, usually by having two metal plates close together but not electrically connected. How do we know it stores charge? At a microscopic level, electrons congregate on one plate and are depleted on the other, in addition, a strong electric field builds up between the two plates.

Ok but you can’t really see or measure either of those effects at home. What you can measure are voltage and current, so for the rest of this post we’ll mostly worry about what the voltage and current are doing.

For a two terminal device like a resistor, capacitor or inductor there are only really two external variables relating to those two terminals:

- What is the (signed) current entering one terminal and exiting the other? Let’s just call this $I$.

- What is the (signed) voltage difference between the terminals? Call this $V$.

Aside: This made me wonder about the possibility of current going into one terminal but not leaving by the other which would be a violation of Kirchhoff’s current law. I think the reason we don’t worry about this is because the timescale over which is electrons equilibrate is so fast that we wouldn’t notice these violations in most conditions, see the lumped element model on wikipedia for more detail on these kinds of assumptions.

The other thing worth noting here is that the hydraulic analogy for a capacitor is not that of a bucket filling with electrons. If you see it like that then you’ll have noticed that that view also violates Kirchhoff’s current law. They’re more like a pipe with a flexible membrane.

Image credit: Sbyrnes321 Wikipedia

Nitpick: Also the membrane follows Hooke’s law so the restoring force (voltage) scales linearly with the volume displaced (charge) and the energy stored scales quadratically with the same. But that’s not so important for a mental model.

For a capacitor in this idealised mathematical model of electrical circuits, it turns out it’s enough to simply ask what the relationship between $V$ and $I$ is. And you can kinda guess what it’s gonna be, the restoring force, voltage, is proportional to the stored charge. Current is the movement of charge over time so we know we probably have to integrate current over time and lastly we know that a bigger capacitor should charge up more slowly than a smaller one for a given current. Putting those together gives us:

\[V = \frac{1}{C} \int I \,dt\]Where we know it has to be $1/C$ rather than $C$ because bigger capacitors charge more slowly. We can also write this in derivative form:

\[V = \frac{1}{C} \int I \,dt \iff I = C\dot{V}\]Capacitors store charge and that stored charge resists changes in voltage across the terminals. Inductors are the dual, they’re like a flywheel that spins up with current and they resist changes in that current based on their inductance. This happens physically because a current creates a magnetic field in which the energy is stored and an inductor is basically a wire wound to have a higher than normal self inductance.

We can ‘spin up’ an inductor by putting a voltage a across it which will cause the current going through it to rise steadily, as with capacitors, bigger inductors take long to spin up.

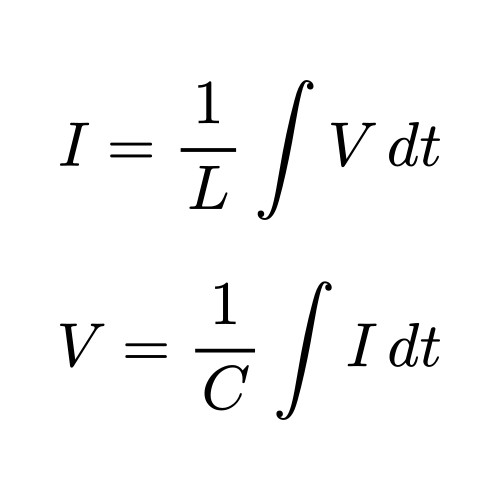

\[I = \frac{1}{L} \int V \,dt \iff V = L\dot{I}\]See how the equations for capacitors and inductors basically take the same form? The only difference is we swap $V$ and $I$ and rename the symbol for how big they are.

When I try to remember webs of knowledge like this, I find it helpful to have a kernel that I know I can memorise correctly, in this case it’s

\[V = \frac{1}{C} \int I \,dt\]because I have a intuitive feeling for a capacitor charging up over time and I know bigger capacitors charge slower. From there I know I will remember that inductors are dual and I can differentiate to get the other forms.

However, it turns out that most of the time we don’t really use differential equations like these to think about capacitance and inductance. That’s the next bit I want to talk about.

Aside: These differential equations can be useful, you can solve them exactly for charging a capacitor from a voltage source and you find that capacitors charge and discharge exponentially. Same deal for inductors supplied from a constant current source but who does that? You can also use these differential equations if you want to do a numerical simulation of a circuit that has non linear elements in it like diodes, transistors… all of modern electronics really.

Complex Impedance

Ok this is the bit I really like. We can write down three governing equations for capacitors, resistors and inductors in the form $V = …$

| Inductor | \(L \dot{I}\) |

| Resistor | \(RI\) |

| Capacitor | \(C^{-1} \int I dt\) |

This form is cute because each time we go down the table we integrate current once with respect to time. This nicely situates resistors in the middle between inductors and capacitors.

Ok the cool idea here is this, we know these equations are all linear differential equations and that has a very useful consequence sinusoidal waveforms will stay sinusoidal when modulated by these components.

Now the undisputed was to represent sinusoidal waveforms is with complex numbers:

\[I(t) = Re \left( \; I_0 \; e^{i \omega t} \right)\] \[V(t) = Re \left( V_0 \; e^{i \omega t} \right)\]$I_0$ and $V_0$ are both complex numbers that encode the magnitude and phase of the current and voltage waveforms that we’re considering. We’re also only considering one frequency $\omega$ at a time but we can vary it to understand how the components behave at different frequencies.

So the trick with complex impedances is this: if we temporarily ignore those $Re()$ operators in the above equations for a minute we can come up with a complex version of Ohm’s law that works for resistors, capacitors and inductors all in one:

\[V = \mathbb{Z} I\]But what is the value of the complex impedance $\mathbb{Z}$? For resistors, it’s easy, it’s just $R$. For capacitors we can rearrange and use the fact that $\int e^{i \omega t} dt = \omega e^{i \omega t} $ to get:

\[\mathbb{Z} = V / I = \frac{1}{i \omega C}\]and similarly for inductors:

\[\mathbb{Z} = V / I = i \omega L\]These expressions tells us two things, for capacitors the voltage lags the current by 90 degrees or a quarter of a cycle and for inductors the opposite. It also tells use that capacitors look like an open circuit at DC and become a dead short at high frequency while for inductors the opposite is true.

This can all be summed up in this table:

| Inductors | Resistors | Capacitors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integral Eqn. | \(I = \frac{1}{L} \int V \,dt\) | \(V = R I\) | \(V = \frac{1}{C} \int I \,dt\) |

| Differential Eqn | \(V = L\dot{I}\) | \(V = R I\) | \(I = C \dot{V}\) |

| \(V = \;...\) | \(V = L\dot{I}\) | \(V = R I\) | \(V = \frac{1}{C} \int I \,dt\) |

| \(\mathbb{Z} =\) | \(i \omega L\) | \(R\) | \((i \omega C)^{-1}\) |

I won’t go into it here but the next thing that makes complex impedances really useful is that the same equations that govern resistors in series and in parallel also carry over to complex impedances. This allows you to easily derive and expression for the frequency dependent behaviour of a complicated network of resistors, capacitors and inductors.